Using Requires Expression in C++20 as a Standalone Feature

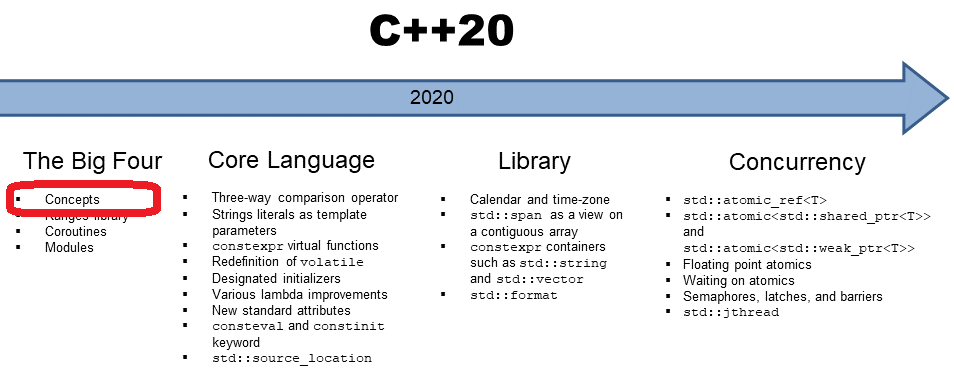

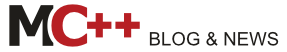

In my last post “Defining Concepts with Requires Expressions“, I exemplified how you can use requires expressions to define concepts. Requires expressions can also be used as a standalone feature when a compile-time predicate is required.

Typical use cases for compile-time predicates are static_assert, constexpr if, or a requires clause. A compile–time predicate is an expression that returns at compile time a boolean. Let me start this post with C++11.

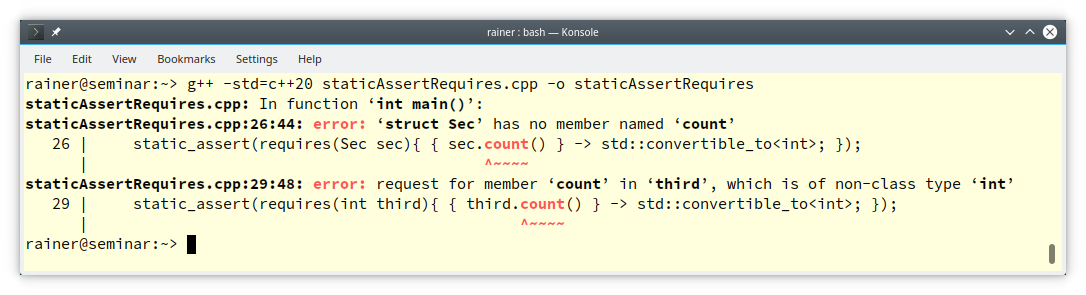

static_assert

static_assert requires a compile-time predicate, and a message is displayed when the compile-time predicate fails. With C++17, the message is optional. With C++20, this compile-time predicates can be a requires expression.// staticAssertRequires.cpp #include <concepts> #include <iostream> struct Fir { // (4) int count() const { return 2020; } }; struct Sec { int size() const { return 2021; } }; int main() { std::cout << '\n'; Fir fir; static_assert(requires(Fir fir){ { fir.count() } -> std::convertible_to<int>; }); // (1) Sec sec; static_assert(requires(Sec sec){ { sec.count() } -> std::convertible_to<int>; }); // (2) int third; static_assert(requires(int third){ { third.count() } -> std::convertible_to<int>; }); // (3) std::cout << '\n'; }

count and if its result is convertible to int. This check is only valid for the class First (lines 4). On the contrary, the checks in lines (2) and (3) fail.

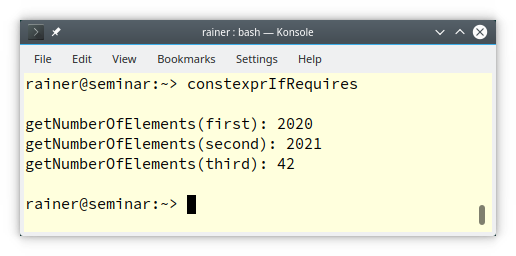

constexpr if combined with requires expressions provides you with the necessary tool.constexpr if

constexpr if allows it to compile source code conditionally. For the condition, the requires expression comes into play. All branches of the if statement have to be valid.constexpr if, you can define functions that inspect their arguments at compile time and generate different functionality based on their analysis.// constexprIfRequires.cpp #include <concepts> #include <iostream> struct First { int count() const { return 2020; } }; struct Second { int size() const { return 2021; } }; template <typename T> int getNumberOfElements(T t) { if constexpr (requires(T t){ { t.count() } -> std::convertible_to<int>; }) { // (1) return t.count(); } if constexpr (requires(T t){ { t.size() } -> std::convertible_to<int>; }) { // (2) return t.size(); } else return 42; // (3) } int main() { std::cout << '\n'; First first; std::cout << "getNumberOfElements(first): " << getNumberOfElements(first) << '\n'; Second second; std::cout << "getNumberOfElements(second): " << getNumberOfElements(second) << '\n'; int third; std::cout << "getNumberOfElements(third): " << getNumberOfElements(third) << '\n'; std::cout << '\n'; }

t has a member function count that returns an int. Accordingly, line (2) determines if the variable t has a member function size. The else statement in line (3) is applied as a fallback.

Requires Clause

First of all, I have to answer the question: What is a requires clause?

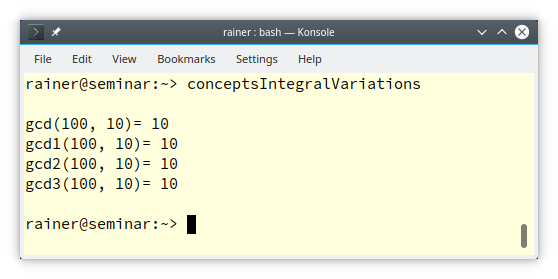

There are essentially four ways to use a concept, such as std::integral.

// conceptsIntegralVariations.cpp #include <concepts> #include <type_traits> #include <iostream> template<typename T> // (1) requires std::integral<T> auto gcd(T a, T b) { if( b == 0 ) return a; else return gcd(b, a % b); } template<typename T> // (2) auto gcd1(T a, T b) requires std::integral<T> { if( b == 0 ) return a; else return gcd1(b, a % b); } template<std::integral T> // (3) auto gcd2(T a, T b) { if( b == 0 ) return a; else return gcd2(b, a % b); } auto gcd3(std::integral auto a, // (4) std::integral auto b) { if( b == 0 ) return a; else return gcd3(b, a % b); } int main(){ std::cout << '\n'; std::cout << "gcd(100, 10)= " << gcd(100, 10) << '\n'; std::cout << "gcd1(100, 10)= " << gcd1(100, 10) << '\n'; std::cout << "gcd2(100, 10)= " << gcd2(100, 10) << '\n'; std::cout << "gcd3(100, 10)= " << gcd3(100, 10) << '\n'; std::cout << '\n'; }

<concepts> I can use the concept std::integral. The concept is fulfilled if T it is integral. The function name gcd stands for the greatest-common-divisor algorithm based on the Euclidean algorithm.- Requires clause (line 1)

- Trailing requires clause (line 2)

- Constrained template parameter (line 3)

- Abbreviated function template (line 4)

auto. There is a semantic difference between the function templates gcd, gcd1, gcd2, and the function gcd3. In the case of gcd, gcd1, or gcd2, arguments a and b must have the same type. This does not hold for the function gcd3. Parameters a and b can have different types but must both fulfill the concept std::integral.

gcd and gcd1 use requires clauses.

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

// requiresClause.cpp #include <iostream> template <unsigned int i> requires (i <= 20) // (1) int sum(int j) { return i + j; } int main() { std::cout << '\n'; std::cout << "sum<20>(2000): " << sum<20>(2000) << '\n', // std::cout << "sum<23>(2000): " << sum<23>(2000) << '\n', // ERROR std::cout << '\n'; }

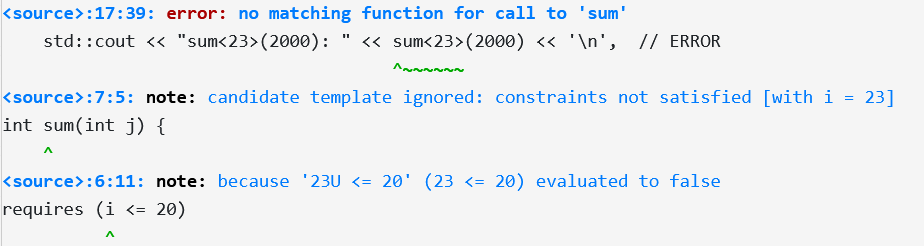

i, and not on a type as usual.main program, the clang compiler reports the following error:

requires requires or anonymous conceptsrequires requires or anonymous concepts

template<typename T> requires requires (T x) { x + x; } auto add(T a, T b) {

return a + b;

}

add uses a requires expression (requires(T x) { x + x; } ) inside a requires clause. The anonymous concept is equivalent to the following concept Addable.template<typename T> concept Addable = requires (T a, T b) { a + b; };

add are equivalent to the previous one:template<typename T> // requires clause requires Addable<T> auto add(T a, T b) { return a + b; } template<typename T> // trailing requires clause auto add(T a, T b) requires Addable<T> { return a + b; } template<Addable T> // constrained template parameter auto add(T a, T b){ return a + b; } // abbreviated function template auto add(Addable auto a, Addable auto b) { return a + b; }

As a short reminder: The last implementation based on abbreviated function templates syntax can deal with values having different types.

Again, I want to emphasize it: Concepts should encapsulate general ideas and give them a self-explanatory name for reuse. They are invaluable for maintaining code. Anonymous concepts read more like syntactic constraints on template parameters and should be avoided.

What’s next?

static_assert(Concept<T>) tests whether the type T fulfills the concept. Let’s see how we can use this in my next post.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Phillip Diekmann, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, schnapper79, Seeker, and Sundareswaran Senthilvel.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!