The Template Method

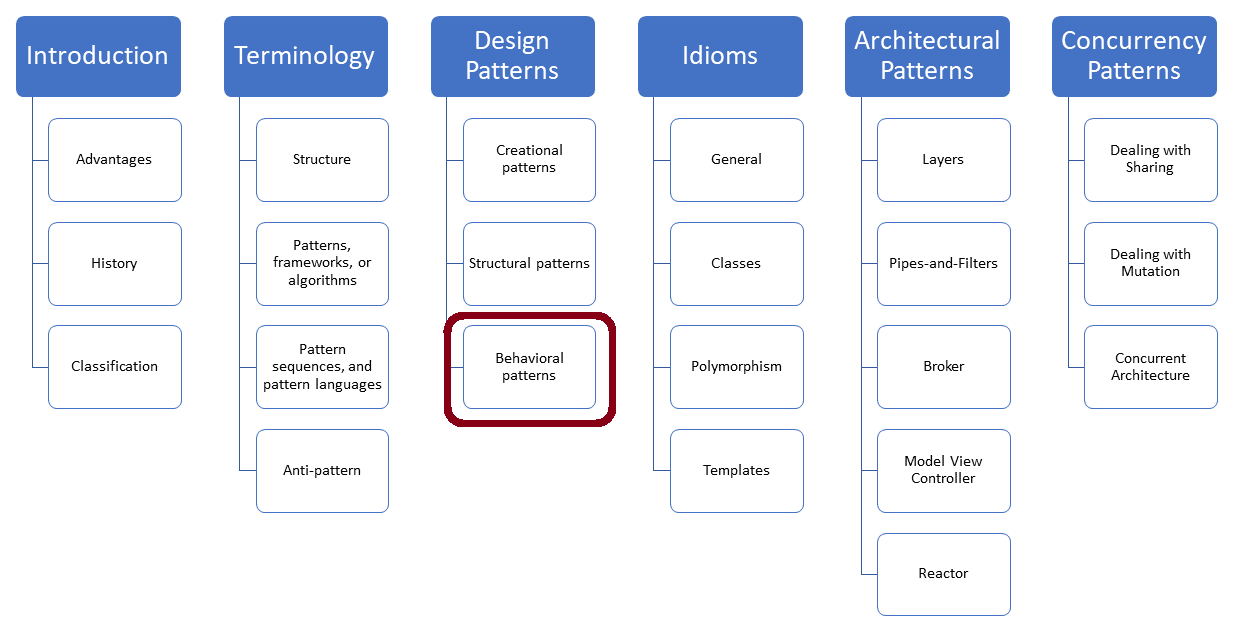

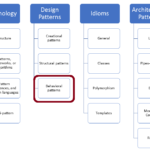

The Template Method is a behavioral design pattern. It defines a skeleton for an algorithm and is probably one of the most often used design patterns from the book “Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software”.

The key idea of the Template Method is easy to get. You define the skeleton of an algorithm that consists of a few typical steps. Implementation classes can only override the steps but cannot change the skeleton. The steps are often called hook methods.

Template Method

Purpose

- Define a skeleton of an algorithm consisting of a few typical steps

- Subclasses can adjust the steps but not the skeleton

Use case

- Different variants of an algorithm should be used

- The variants of an algorithm consist of similar steps

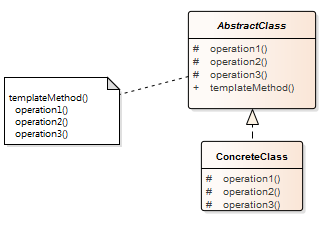

Structure

AbstractClass

- Defines the structure of the algorithm, consisting of various steps

- The steps of the algorithm can be virtual or pure virtual

ConcreteClass

- Overwrites the specific steps of the algorithm if necessary

Example

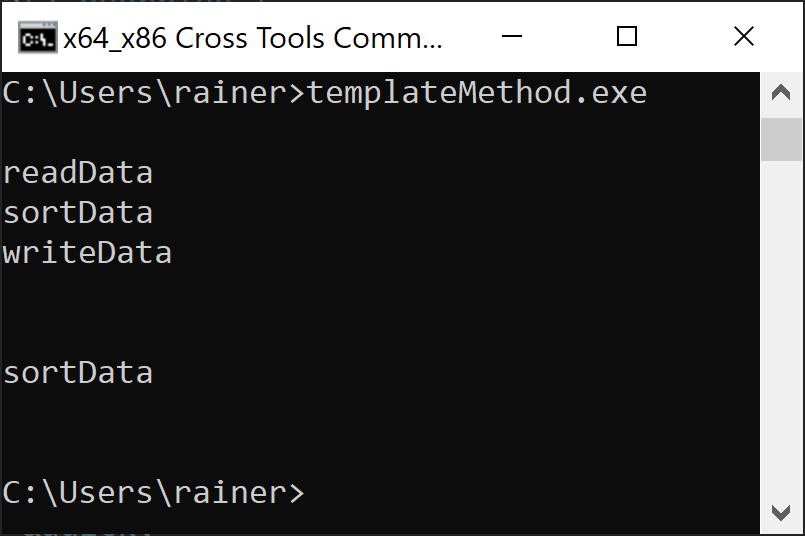

The following program templateMethod.cpp exemplifies the structure of the Template Method.

// templateMethod.cpp #include <iostream> class Sort{ public: virtual void processData() final { // (4) readData(); sortData(); writeData(); }

virtual ~Sort() = default; private: virtual void readData(){} // (1) virtual void sortData()= 0; // (2) virtual void writeData(){} // (3) }; class QuickSort: public Sort{ void readData() override { std::cout << "readData" << '\n'; } void sortData() override { std::cout << "sortData" << '\n'; } void writeData() override { std::cout << "writeData" << '\n'; } }; class BubbleSort: public Sort{ void sortData() override { std::cout << "sortData" << '\n'; } }; int main(){ std::cout << '\n'; QuickSort quick; Sort* sort = &quick; // (5) sort->processData(); std::cout << "\n\n"; BubbleSort bubble; sort = &bubble; // (6) sort->processData(); std::cout << '\n'; }

Sorting consists of three steps: readData (line 1), sortData (line 2), and writeData (line 3). The member functions readData() and writeData provide a default implementation, but the member function sortData() is pure virtual. These three steps are the skeleton of the algorithm processData (line 4). Now, quicksort (line 5), and bubble sort (line 6) can be applied.

Here is the output of the program:

I implemented the skeleton function processData and its three steps as a virtual function. Thanks to the three virtual member functions, late binding kicks in, and the member functions of the run-time object are called. On the contrary, making the skeleton function virtual and declaring it as final, is overkill in C++. final means that a virtual function cannot be overridden.

When a member function should not be overridable, make it non-virtual.

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

Non-Virtual Interface (NVI) Idiom

The idiomatic way to implement the Template Method in C++ is to apply the Non-Virtual Interface Idiom. Non-Virtual Interface means that the skeleton is non-virtual, and the steps are virtual. Because the client uses the interface, the skeleton cannot be changed. Here is the corresponding implementation of the interface Sort:

class Sort{ public: void processData() { readData(); sortData(); writeData(); } private: virtual void readData(){} virtual void sortData()= 0; virtual void writeData(){} };

Herb Sutter made the NVI in 2001 popular in C++. Virtuality.

In his article Virtuality, he boiled the NVI down to four guidelines:

- Guideline #1: Prefer to make interfaces nonvirtual, using Template Method design pattern.

- Guideline #2: Prefer to make virtual functions private.

- Guideline #3: Only if derived classes need to invoke the base implementation of a virtual function, make the virtual function protected.

- Guideline #4: A base class destructor should be either public and virtual, or protected and nonvirtual.

Related Patterns

- The Template Method and Strategy Pattern use cases are pretty similar. Both patterns enable it to provide variations of an algorithm. The Template Method is based on a class level by subclassing, and the Strategy Pattern on an object level by composition. The Strategy Pattern gets is various strategies as objects and can, therefore, exchange its strategies at run time. The Template Method inverts the control flow, following the Hollywood principle: “Don’t call us, we call you. The Strategy Pattern is often a black box. It allows you to replace one strategy with another without knowing its details.

- The Factory Method is often called in specific steps of the Template Method.

Pros and Cons

Pros

- New variations of an algorithm are easy to implement by creating new subclasses

- Common steps of the algorithms can be implemented directly in the interface class

Cons

- Now, even small variations of an algorithm require the creation of a new class; this may lead to the creation of many small classes

- The skeleton is fixed and cannot be changed; you can overcome this limitation by making the skeleton function virtual

What’s Next?

Only one pattern from the book “Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software” is missing in my journey: the Strategy Pattern. The Strategy Pattern is heavily used in the Standard Template Library. I will write about the Strategy Pattern in my next post.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Phillip Diekmann, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, schnapper79, Seeker, and Sundareswaran Senthilvel.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

If the processData() method is not declared virtual and final, a version of processData() could be written for each derived class. In such a case, if we implement processData() in the QuickSort class, the sort->processData() statement would invoke the QuickSort processData() method. Isn’t this counter-intuitive

This cannot happen. You use

QuickSortwith the interface ofSort. Consequentially,QuickSortsprocessDatamember function is ignored.