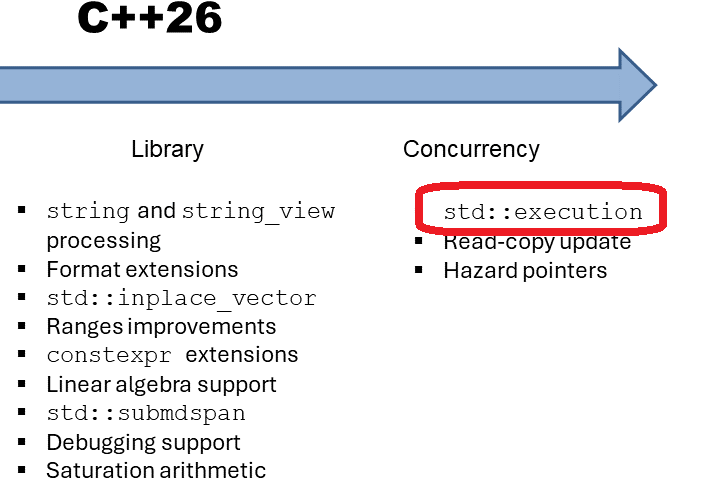

std::execution

std::execution, previously known as executors or Senders/Receivers, provides “a Standard C++ framework for managing asynchronous execution on generic execution resources“. (P2300R10)

Side Note

Change of plans. My original plan was to present the C++26 library after the core language. However, the implementation status of the library is not good enough. Therefore, I decided to continue with concurrency and std::execution. I will present the remaining C++26 features if a compiler implements them.std::execution

std::execution has three key abstractions: schedulers, senders, and receivers, and a set of customizable asynchronous algorithms. My presentation of std::execution is based on the proposal P2300R10.

First Experiments

I used stdexec for my first experiments. This reference implementation from NVIDIA is based on the eighth revision of the proposal. The purpose of this experiment can be found on GitHub.

- Provide a proof-of-concept implementation of the design proposed in P2300.

- Provide early access to developers looking to experiment with the Sender model.

- Collaborate with those interested in participating or contributing to the design of P2300 (contributions welcome!).

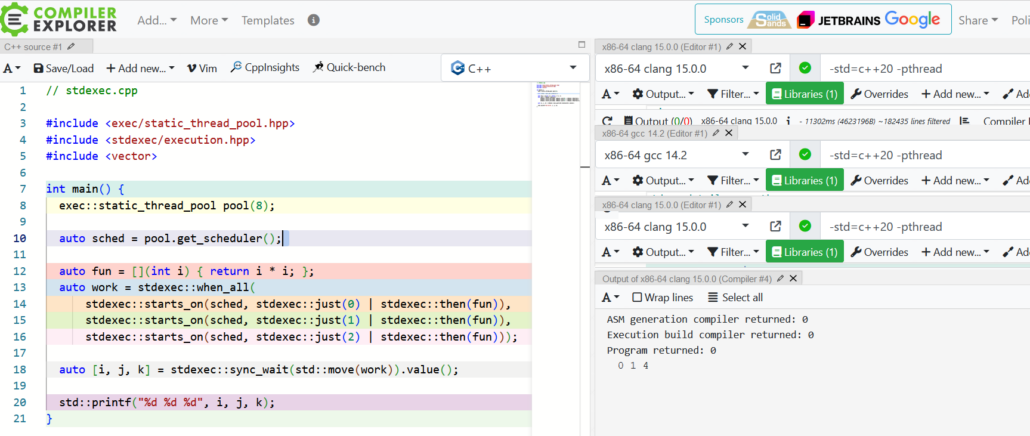

You can try out stdexec on godbolt with the following program.

#include <stdexec/execution.hpp> #include <exec/static_thread_pool.hpp> int main() { // Declare a pool of 3 worker threads: exec::static_thread_pool pool(3); // Get a handle to the thread pool: auto sched = pool.get_scheduler(); // Describe some work: // Creates 3 sender pipelines that are executed concurrently by passing to `when_all` // Each sender is scheduled on `sched` using `on` and starts with `just(n)` that creates a // Sender that just forwards `n` to the next sender. // After `just(n)`, we chain `then(fun)` which invokes `fun` using the value provided from `just()` // Note: No work actually happens here. Everything is lazy and `work` is just an object that statically // represents the work to later be executed auto fun = [](int i) { return i*i; }; auto work = stdexec::when_all( stdexec::starts_on(sched, stdexec::just(0) | stdexec::then(fun)), stdexec::starts_on(sched, stdexec::just(1) | stdexec::then(fun)), stdexec::starts_on(sched, stdexec::just(2) | stdexec::then(fun)) ); // Launch the work and wait for the result auto [i, j, k] = stdexec::sync_wait(std::move(work)).value(); // Print the results: std::printf("%d %d %d\n", i, j, k); }

Let me convert this program into the revision 10 syntax. You can also try it out on godbolt.

The program begins by including the necessary headers: <exec/static_thread_pool.hpp> for creating a thread pool, <stdexec/execution.hpp> for execution-related utilities.

In the main function, a static_thread_pool pool is created with 8 threads. The thread pool executes tasks concurrently. The get_scheduler member function of the thread pool is called to obtain a scheduler object sched. The schedule schedules the tasks on the thread pool.

The lambda function fun takes an integer i as input and returns its square (i * i). This lambda is applied to the input values in the subsequent tasks.

The stdexec::when_all function creates a task that waits for the completion of multiple sub-tasks. Each sub-task is created using the stdexec::starts_on function, which schedules the task on the specified scheduler sched. The stdexec::just function creates a task that produces a single value (0, 1, or 2), and the stdexec::then function is used to apply the fun lambda to this value. The resulting task object is named work.

The stdexec::sync_wait function is then called to wait for the completion of the task synchronously. The std::move function transfers ownership of the work task to sync_wait. The value member function is called on the result of sync_wait to obtain the values produced by the sub-tasks. These values are unpacked into the variables i, j, and k.

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

Finally, the program prints the values of i, j, and k to the console using std::printf. These values represent the squares of 0, 1, and 2, respectively.

The following screenshot shows the execution of the program on the Compiler Explorer:

I wrote at the beginning of this post that std::execution has three key abstractions: schedulers, senders, and receivers, and a set of customizable asynchronous algorithms. Let me clarify these abstractions:

Execution resources

- represent the place of execution

- don‘t need a representation in code

Scheduler: sched

- represent the execution resource

- The scheduler concept is defined by a single sender algorithm:

schedule. - The algorithm schedule returns a sender that will complete on an execution resource determined by the scheduler.

Sender describes work: when_all, starts_on, just, then

- send some values if a receiver connected to that sender will eventually receive said values

justis a so-called sender factory

Receiver stops the workflow: sync_wait

- it supports three channels: value, error, stopped

sync_waitit’s a so-called sender consumer- submits the work, blocking the current

std::threadand returns an optional tuple of values that were sent by the provided sender on its completion of work

What’s Next?

After this introduction, I will dive deeper into the set of customizable asynchronous algorithms and preset further examples.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, schnapper79, Seeker, and Sundareswaran Senthilvel.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org