Semaphores in C++20

Semaphores are a synchronization mechanism used to control concurrent access to a shared resource. They also allow it to play ping-pong.

A counting semaphore is a special semaphore with a counter bigger than zero. The counter is initialized in the constructor. Acquiring the semaphore decreases the counter, and releasing the semaphore increases the counter. If a thread tries to acquire the semaphore when the counter is zero, the thread will block until another thread increments the counter by releasing the semaphore.

Edsger W. Dijkstra Invented Semaphores

The Dutch computer scientist Edsger W. Dijkstra presented 1965 the concept of a semaphore. A semaphore is a data structure with a queue and a counter. The counter is initialized to a value equal to or greater than zero. It supports the two operations wait and signal. wait acquires the semaphore and decreases the counter; it blocks the thread acquiring it if the counter is zero. signal releases the semaphore and increases the counter. Blocked threads are added to the queue to avoid starvation.

Originally, a semaphore is a railway signal.

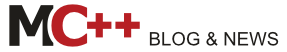

Counting Semaphores in C++20

C++20 supports a std::binary_semaphore, which is an alias for a std::counting_semaphore<1>. In this case, the least maximal value is 1. std::binary_semaphores can be used to implement locks.

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

using binary_semaphore = std::counting_semaphore<1>;

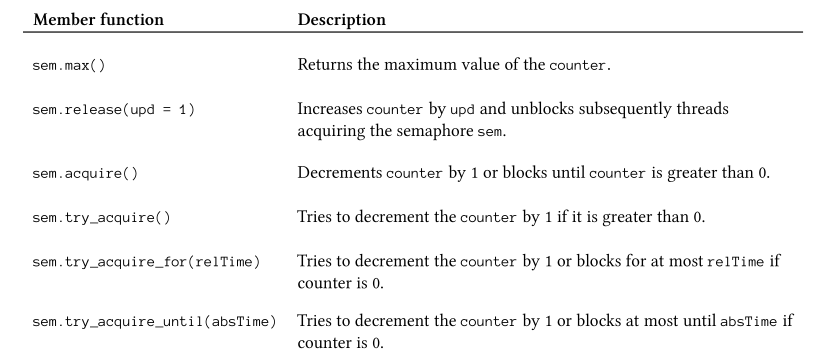

In contrast to a std::mutex, a std::counting_semaphore is not bound to a thread. This means that the acquire and release call of a semaphore can happen on different threads. The following table presents the interface of a std::counting_semaphore.

The constructor call std::counting_semaphore<10> sem(5) creates a semaphore sem with a maximal value of 10 and a counter of 5. The call sem.max() returns the least maximal value. sem.try_aquire_for(relTime) needs a relative time duration; the member function sem.try_acquire_until(absTime) needs an absolute time point. In my previous posts, you can read more about time durations and time points to the time library: time. The three calls sem.try_acquire, sem.try_acquire_for, and sem.try_acquire_until return a boolean indicating the success of the calls.

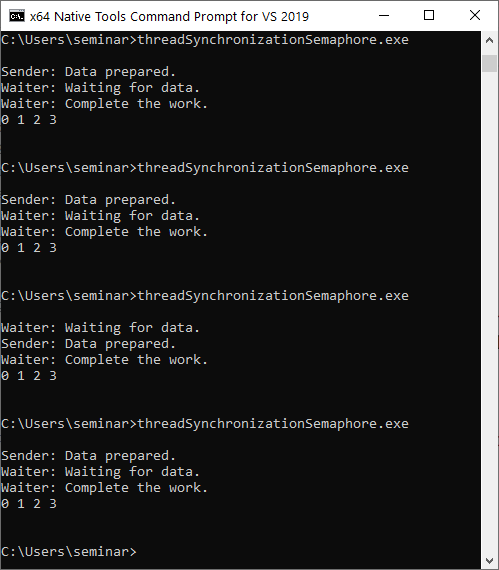

Semaphores are typically used in sender-receiver workflows. For example, initializing the semaphore sem with 0 will block the receiver sem.acquire() call until the sender calls sem.release(). Consequently, the receiver waits for the notification of the sender. A one-time synchronization of threads can easily be implemented using semaphores.

// threadSynchronizationSemaphore.cpp #include <iostream> #include <semaphore> #include <thread> #include <vector> std::vector<int> myVec{}; std::counting_semaphore<1> prepareSignal(0); // (1) void prepareWork() { myVec.insert(myVec.end(), {0, 1, 0, 3}); std::cout << "Sender: Data prepared." << '\n'; prepareSignal.release(); // (2) } void completeWork() { std::cout << "Waiter: Waiting for data." << '\n'; prepareSignal.acquire(); // (3) myVec[2] = 2; std::cout << "Waiter: Complete the work." << '\n'; for (auto i: myVec) std::cout << i << " "; std::cout << '\n'; } int main() { std::cout << '\n'; std::thread t1(prepareWork); std::thread t2(completeWork); t1.join(); t2.join(); std::cout << '\n'; }

The std::counting_semaphore prepareSignal (1) can have the values 0 or 1. The concrete example initializes it with 0 (line 1). This means that the call prepareSignal.release() sets the value to 1 (line 2) and unblocks the call prepareSignal.acquire() (line 3).

Let me make a small performance test by playing ping-pong with semaphores.

A Ping-Pong Game

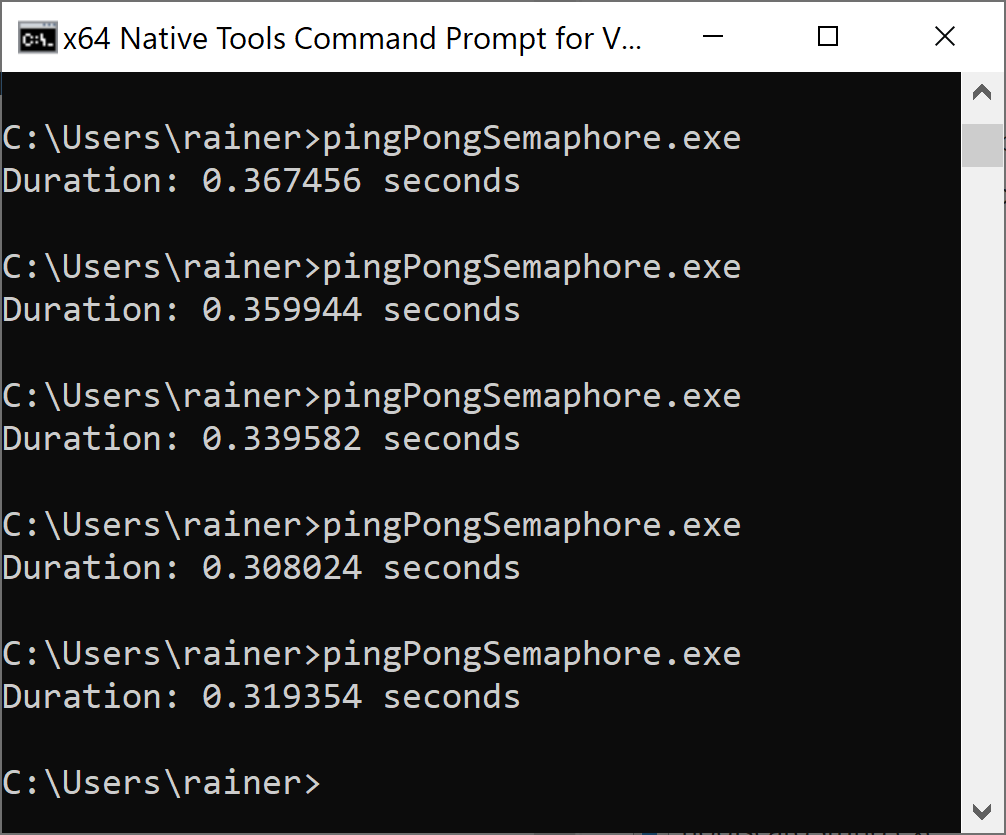

In my last post, “Performance Comparison of Condition Variables and Atomics in C++20“, I implemented a ping-pong game. Here is the idea of the game: One thread executes a ping function and the other thread a pong function. The ping thread waits for the notification of the pong thread and sends the notification back to the pong thread. The game stops after 1,000,000 ball changes. I perform each game five times to get comparable performance numbers. Let’s start the game:

// pingPongSemaphore.cpp #include <iostream> #include <semaphore> #include <thread> std::counting_semaphore<1> signal2Ping(0); // (1) std::counting_semaphore<1> signal2Pong(0); // (2) std::atomic<int> counter{}; constexpr int countlimit = 1'000'000; void ping() { while(counter <= countlimit) { signal2Ping.acquire(); // (5) ++counter; signal2Pong.release(); } } void pong() { while(counter < countlimit) { signal2Pong.acquire(); signal2Ping.release(); // (3) } } int main() { auto start = std::chrono::system_clock::now(); signal2Ping.release(); // (4) std::thread t1(ping); std::thread t2(pong); t1.join(); t2.join(); std::chrono::duration<double> dur = std::chrono::system_clock::now() - start; std::cout << "Duration: " << dur.count() << " seconds" << '\n'; }

The program pingPongsemaphore.cpp uses two semaphores: signal2Ping and signal2Pong (1 and 2). Both can have the two values 0 and 1 and are initialized with 0. This means when the value is 0 for the semaphore signal2Ping, a call signal2Ping.release() (3 and 4) set the value to 1 and is, therefore, a notification. A signal2Ping.acquire() (5) call blocks until the value becomes 1. The same argumentation holds for the second semaphore signal2Pong.

On average, the execution time is 0.33 seconds.

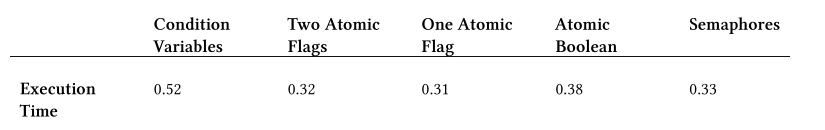

Let me summarize the performance numbers for all ping-pong games. This includes the performance numbers of my last post, “Performance Comparison of Condition Variables and Atomics in C++20” and this ping-pong game implemented with semaphores.

All Numbers

Condition variables are the slowest way, and atomic flag the fastest way to synchronize threads. The performance of a std::atomic is in between. There is one downside with std::atomic. std::atomic_flag is the only atomic data type that is always lock-free. Semaphores impressed me most because they are nearly as fast as atomic flags.

What’s next?

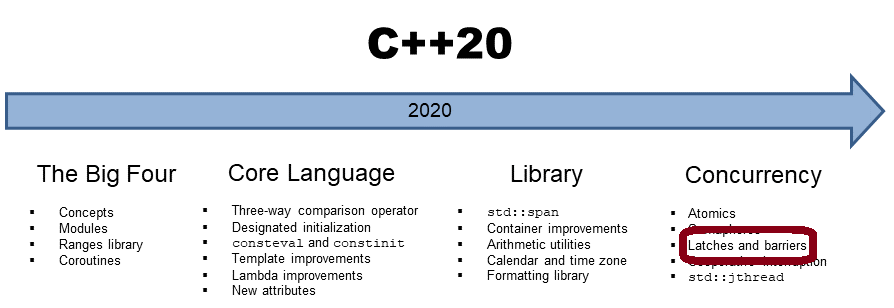

With latches and barriers, we have more convenient coordination types in C++20. Let me present them in my next post.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Phillip Diekmann, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, schnapper79, Seeker, and Sundareswaran Senthilvel.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!