Hash Tables

We missed the hash table in C++ for a long time. They promise to have constant access time. C++11 has hash tables in four variations. The official name is unordered associative containers. Unofficially, they are called dictionaries or just simple associative arrays.

Classical C++ has four different associative containers. With C++11, we get four additional ones. First, we need a systematic.

Associative container

All associative containers have in common that they associated a key with a value. Therefore, you can get the value by using the key. The classical associative containers are called ordered associative containers; the new ones are unordered associative containers.

Ordered associative containers

The small difference is that the keys of the classical associative containers are ordered. By default, the smaller relation (<) is used. Therefore, the containers are sorted in increasing order.

This ordering has exciting consequences for the ordered associative containers.

- The key has to support an ordering relation.

- Associative containers are typically implemented in balanced binary search trees.

- The access time to the key and, therefore, to the value is logarithmic.

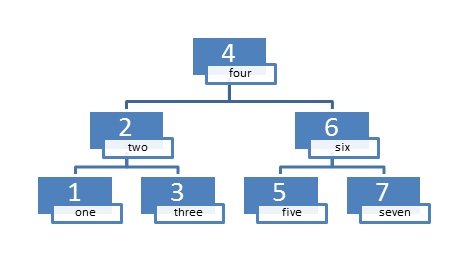

The most often used ordered associative container is std::map:

map<int, string> int2String{ {3,"three"},{2,"two"},{1,"one"},{5,"five"},{6,"six"},{4,"four"},{7,"seven"} };

The balanced binary search tree may have the following structure.

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

Unordered associative containers

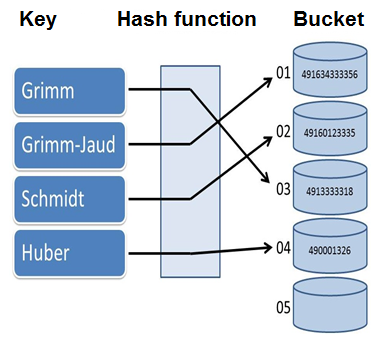

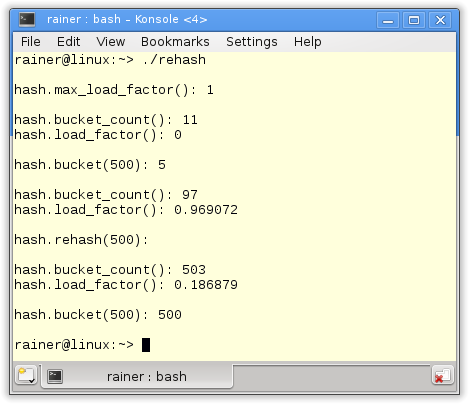

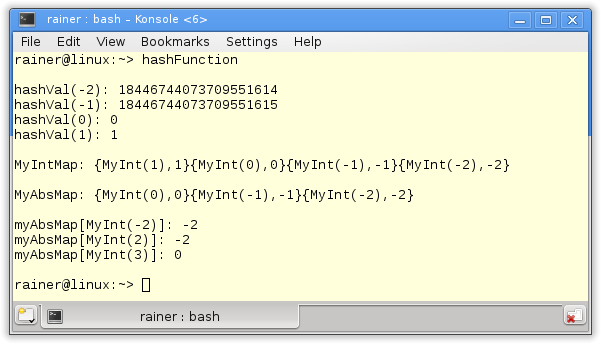

The key idea of the unordered associative containers is that the key is mapped with the help of the hash function onto the bucket. You can find the key/value pair in the bucket.

I have to introduce a few terms before I describe the characteristics of unordered associative containers.

- Hash value: The value you will get if you apply the hash function to the key.

- Collision: We will collide if different keys are mapped to the same hash value. The unordered associative containers have to deal with this situation.

The usage of the hash function has very important consequences for the unordered associative container.

- The keys have to support equal comparison to deal with collisions.

- The hash value of a key has to be available.

- The execution of a hash function is a constant. Therefore, the access time to the keys of an unordered associative container is constant. For simplicity reasons I ignored collisions.

According to std::map is the most often used ordered associative container std::unordered_map will become the most often used unordered associative container.

unordered_map<string,int> str2Int{ {"Grimm",491634333356},{"Grimm-Jaud",49160123335}, {"Schmidt",4913333318},{"Huber",490001326} };

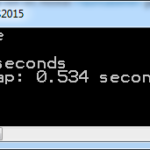

The graphic shows the mapping of the keys to their bucket by using the hash function.

The similarities

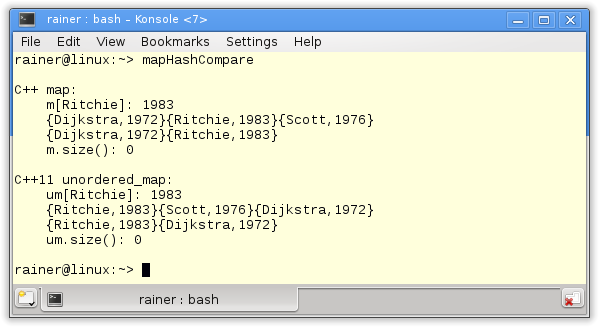

The similar names of std::map and std::unordered_map are not by accident. Both have a similar interface. To be more precise. The interface of std::map is a subset of the interface of std::unorederd_map. Have a look:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 |

// mapHashCompare.cpp #include <iostream> #include <map> #include <unordered_map> int main(){ std::cout << std::endl; std::cout << "C++ map: " << std::endl; std::map<std::string,int> m { {"Dijkstra",1972},{"Scott",1976} }; m["Ritchie"] = 1983; std::cout << " m[Ritchie]: " << m["Ritchie"] << "\n "; for(auto p : m) std::cout << '{' << p.first << ',' << p.second << '}'; m.erase("Scott"); std::cout << "\n "; for(auto p : m) std::cout << '{' << p.first << ',' << p.second << '}'; m.clear(); std::cout << std::endl; std::cout << " m.size(): " << m.size() << std::endl; std::cout << std::endl; std::cout << "C++11 unordered_map: " << std::endl; std::unordered_map<std::string,int> um { {"Dijkstra",1972},{"Scott",1976} }; um["Ritchie"] = 1983; std::cout << " um[Ritchie]: " << um["Ritchie"] << "\n "; for(auto p : um) std::cout << '{' << p.first << ',' << p.second << '}'; um.erase("Scott"); std::cout << "\n "; for(auto p : um) std::cout << '{' << p.first << ',' << p.second << '}'; um.clear(); std::cout << std::endl; std::cout << " um.size(): " << um.size() << std::endl; std::cout << std::endl; } |

The keys of the std::maps are ordered and, therefore, the pairs. Surprised? Of course not! That is the visible difference between the ordered and unordered associative containers.

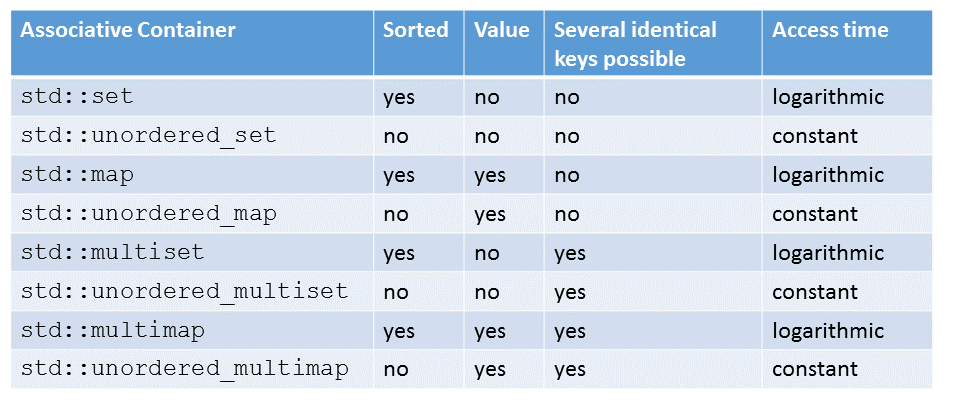

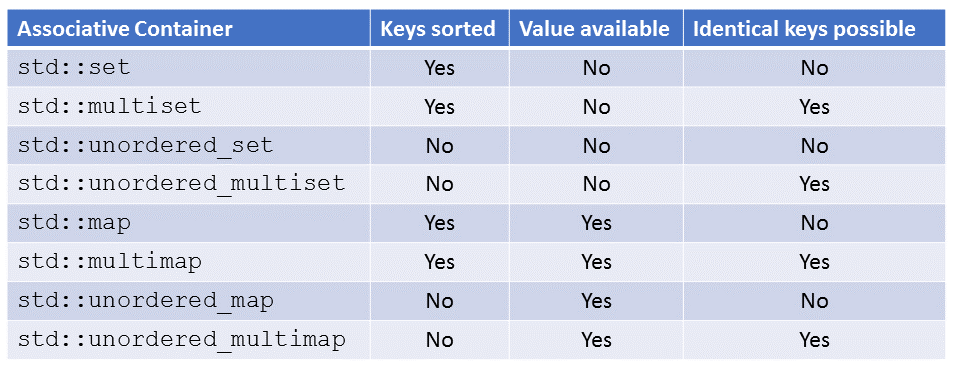

The eight variations

I start with the classically ordered associative containers to get an ordering into the eight variations. You can easily apply the ordering to the unordered associative containers.

The answers to two questions are the key to getting systematic into ordered associative containers:

- Does the key have an associated value?

- Are several identical keys possible?

You get the four ordered associative containers std::set, std::multiset, std::map, and std::multimap by answering the two questions.

Of course, you can apply the two questions to the unordered associative containers. Now you get the containers std::unordered_set, std::unordered_multiset, std::unordered_map, and std::unordered_multimap.

All that is left is to write down the systematic. If the container’s name has the component

- map, it has an associated value.

- multi, it can have more than one identical key.

- unordered, its keys are non-sorted.

But the analogy goes on. If two container names only differ in the name component unordered, they will have a similar interface. The container without the name component unordered supports an interface that is a subset of the unordered container. You saw it already in the listing mapHashCompare.cpp.

The table shows once more the entire system. The systematic includes the access time for the ordered containers (logarithmic) and the unordered container (constant).

What’s next?

My first plan was to show you the performance difference between ordered and unordered containers. So, I will do it in the next post.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Phillip Diekmann, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, and Seeker.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!