C++ Core Guidelines: More Rules about Class Hierarchies

In the last post, I started our journey with the rules of class hierarchies in modern C++. The first rules had a pretty general focus. This time, I will continue our journey. Now, the rules have a closer focus.

Here are the rules for class hierarchies.

- C.126: An abstract class typically doesn’t need a constructor

- C.127: A class with a virtual function should have a virtual or protected destructor

- C.128: Virtual functions should specify exactly one of

virtual,override, orfinal - C.129: When designing a class hierarchy, distinguish between implementation inheritance and interface inheritance

- C.130: Redefine or prohibit copying for a base class; prefer a virtual

clonefunction instead - C.131: Avoid trivial getters and setters

- C.132: Don’t make a function

virtualwithout reason - C.133: Avoid

protecteddata - C.134: Ensure all non-

constdata members have the same access level - C.135: Use multiple inheritance to represent multiple distinct interfaces

- C.136: Use multiple inheritance to represent the union of implementation attributes

- C.137: Use

virtualbases to avoid overly general base classes - C.138: Create an overload set for a derived class and its bases with

using - C.139: Use

finalsparingly - C.140: Do not provide different default arguments for a virtual function and an overrider

Let’s continue with the fourth one.

C.129: When designing a class hierarchy, distinguish between implementation inheritance and interface inheritance

At first, what is the difference between implementation inheritance and interface inheritance? The guidelines give a definite answer. Let me cite it.

- interface inheritance is the use of inheritance to separate users from implementations, in particular, to allow derived classes to be added and changed without affecting the users of base classes.

- implementation inheritance is the use of inheritance to simplify the implementation of new facilities by making useful operations available for implementers of related new operations (sometimes called “programming by difference”).

Pure interface inheritance will occur if your interface class only has pure virtual functions. In contrast, you have an implementation inheritance if your base class has data members or implemented functions. The guidelines give an example of mixing both concepts.

class Shape { // BAD, mixed interface and implementation public: Shape(); Shape(Point ce = {0, 0}, Color co = none): cent{ce}, col {co} { /* ... */} Point center() const { return cent; } Color color() const { return col; } virtual void rotate(int) = 0; virtual void move(Point p) { cent = p; redraw(); } virtual void redraw(); // ... public: Point cent; Color col; }; class Circle : public Shape { public: Circle(Point c, int r) :Shape{c}, rad{r} { /* ... */ } // ... private: int rad; }; class Triangle : public Shape { public: Triangle(Point p1, Point p2, Point p3); // calculate center // ... };

Why is the class Shape bad?

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

- The more the class grows, the more difficult and error-prone it may become to maintain the various constructors.

- The functions of the Shape class may never be used.

- If you add data to the Shape class, a recompilation may become probable.

Shape wouldn’t need a constructor if it were a pure interface consisting only of pure virtual functions. Of course, with a pure interface, you must implement all functionality in the derived classes.

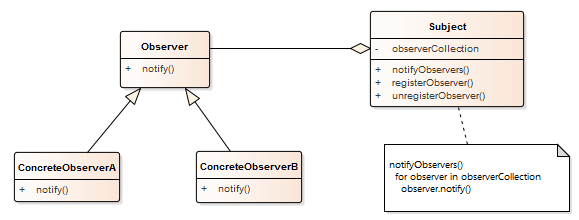

How can we get the best of two worlds: stable interfaces with interface hierarchies and code reuse with implementation inheritance? One possible answer is dual inheritance. Here is a pretty sophisticated receipt for doing it.

1. Define the base Shape of the class hierarchy as a pure interface

class Shape { // pure interface public: virtual Point center() const = 0; virtual Color color() const = 0; virtual void rotate(int) = 0; virtual void move(Point p) = 0; virtual void redraw() = 0; // ... };

2. Derive a pure interface Circle from the Shape

class Circle : public virtual ::Shape { // pure interface public: virtual int radius() = 0; // ... };

3. Provide the implementation class Impl::Shape

class Impl::Shape : public virtual ::Shape { // implementation public: // constructors, destructor // ... Point center() const override { /* ... */ } Color color() const override { /* ... */ } void rotate(int) override { /* ... */ } void move(Point p) override { /* ... */ } void redraw() override { /* ... */ } // ... };

4. Implement the class Impl::Circle by inheriting from the interface and the implementation

class Impl::Circle : public virtual ::Circle, public Impl::Shape { // implementation public: // constructors, destructor int radius() override { /* ... */ } // ... };

5. If you want to extend the class hierarchy, you have to derive from the interface and the implementation

The class Smiley is a pure interface derived from Circle. The class Impl::Smiley is the new implementation, public derived from Smiley and Impl::Circle.

class Smiley : public virtual Circle { // pure interface public: // ... }; class Impl::Smiley : public virtual ::Smiley, public Impl::Circle { // implementation public: // constructors, destructor // ... }

Here is once more the big picture of the two hierarchies.

- interface: Smiley -> Circle -> Shape

- implementation: Impl::Smiley -> Imply::Circle -> Impl::Shape

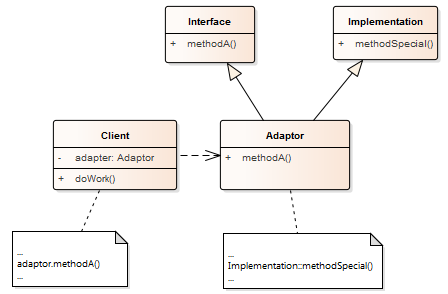

By reading the last lines, maybe you had a déjà vu. You are right. This technique of multiple inheritances is similar to the adapter pattern, implemented with multiple inheritances. The adapter pattern is from the well-known design pattern book.

The idea of the adapter pattern is to translate an interface into another interface. You achieve this by inheriting public from the new interface and private from the old one. That means you use the old interface as an implementation.

C.130: Redefine or prohibit copying for a base class; prefer a virtual clone function instead

I can make it relatively short. Rule C.67 gives a reasonable explanation for this rule.

C.131: Avoid trivial getters and setters

If a trivial getter or setter provides no semantic value, publicize the data item. Here are two examples of trivial getters and setters:

class Point { // Bad: verbose int x; int y; public: Point(int xx, int yy) : x{xx}, y{yy} { } int get_x() const { return x; } void set_x(int xx) { x = xx; } int get_y() const { return y; } void set_y(int yy) { y = yy; } // no behavioral member functions };

x and y can have an arbitrary value. This means an instance of Point maintains no invariant on x and y. x and y are just values. Using a struct as a collection of values is more appropriate.

struct Point { int x {0}; int y {0}; };

C.132: Don’t make a function virtual without reason

This is quite obvious. A virtual function is a feature that you will not get for free.

A virtual function

- increases the run-time and the object code-size

- is open for mistakes because it can be overwritten in derived classes

C.133: Avoid protected data

Protected data make your program complex and error-prone. If you put protected data into a base class, you can not reason about derived classes in isolation and, therefore, you break encapsulation. You always have to reason about the whole class hierarchy.

This means you have to answer at least these three questions.

- Do I have to implement a constructor to initialize the protected data?

- What is the actual value of the protected data if I use them?

- Who will be affected if I modify the protected data?

Answering these questions becomes more and more complicated the more extensive your class hierarchy becomes.

If you think about it: protected data is a kind of global data in the scope of the class hierarchy. And you know, non-const global data is terrible.

Here is the interface Shape enriched with protected data.

class Shape { public: // ... interface functions ... protected: // data for use in derived classes: Color fill_color; Color edge_color; Style st; };

What’s next

We are not done with the rules for class hierarchies, and therefore, I will continue with my tour in the next post.

I have to make a personal confession. I learned a lot by paraphrasing the C++ core guidelines rules and providing more background info if that was necessary from my perspective. I hope the same will hold for you. I would be happy to get comments. So, what’s your opinion?

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Phillip Diekmann, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, and Seeker.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!