C++ Core Guidelines: Function Definitions

Functions are the “fundamental building block of programs.” and “the most critical part in most interfaces.” These statements introduce the rules to function of the C++ core guidelines. Of course, both statements are right. So, let’s dive deeper into the more than 30 rules for defining functions, passing arguments to functions, and returning values from functions.

I will not write about each rule in depth because there are too many rules. I will try to make a story out of the rules. Therefore, you and I can keep them in mind. Let’s start with the rules for defining functions. Here is an overview.

- F.1: “Package” meaningful operations as carefully named functions

- F.2: A function should perform a single logical operation

- F.3: Keep functions short and simple

- F.4: If a function may have to be evaluated at compile time, declare it

constexpr - F.5: If a function is very small and time-critical, declare it inline

- F.6: If your function may not throw, declare it

noexcept - F.7: For general use, take

T*orT&arguments rather than smart pointers - F.8: Prefer pure functions

- F.9: Unused parameters should be unnamed

Function definitions

F.1: “Package” meaningful operations as carefully named functions

F.2: A function should perform a single logical operation

F.3: Keep functions short and simple

The first three rules are pretty obvious and share a common idea. I will start with rule F2. If you write a function that performs a single logical operation (F2), the function will become short and straightforward with a high likelihood (F3). The rules talk about functions that should fit on a screen. Now, you have these short and simple functions that do exactly one logical operation, and you should carefully give them names (F1). These carefully named functions are the basic building blocks to combine and build higher abstractions. Now, you have well-named functions and can easily reason about your program.

F.4: If a function may have to be evaluated at compile-time, declare it constexpr

A constexpr function is a function that can run at compile time or run time. If you invoke a constexpr function with constant expressions and ask for the result at compile-time, you will get it at compile-time. If you invoke the constexpr function with arguments that can not be evaluated at compile-time, you can use it as an ordinary runtime function.

constexpr int min(int x, int y) { return x < y ? x : y; } constexpr auto res= min(3, 4); int first = 3; auto res2 = min(first, 4);

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

The function min has the potential to run at compile time. If I invoke min with constant expressions and ask for the result at compile-time, I will get it at compile-time: constexpr auto res= min(3, 4). I have to use min as an ordinary function because first is not a constant expression: auto res2 = min(first, 4).

There is a lot more to constexpr functions. Their syntax was somewhat limited with C++11, and they became pretty comfortable with C++14. They are a kind of pure function in C++. See my posts about constexpr.

F.5: If a function is very small and time-critical, declare it inline

I was astonished to read this rule because the optimizer will inline functions that are not declared inline, and the other way around: they will not inline functions, although you declare them as inline. In the end, inline is only a hint for the optimizer.

constexpr implies inline. The same holds, by default, true for member functions defined in the class or function templates.

With modern compilers, the main reason for using inline is to break the One Definition Rule (ODR). You can define an inline function in more than one translation unit. Here is my post about inline.

F.6: If your function may not throw, declare it noexcept

By declaring a function as noexcept, you reduce the number of alternative control paths; therefore, noexecpt is a valuable hint to the optimizer.

Even if your function can throw, noexcept often makes a lot of sense. noexcept means in such case: I don’t care. The reason may be that you cannot react to an exception. Therefore, the only way to deal with exceptions is that terminate() will be invoked.

Here is an example of afunction declared as noexcept that may throw because the program may run out of memory.

vector<string> collect(istream& is) noexcept { vector<string> res; for (string s; is >> s;) res.push_back(s); return res; }

F.7: For general use, take T* or T& arguments rather than smart pointers

You restrict the usage of your functions by using Smart Pointers. The example makes the point clear.

// accepts any int* void f(int*); // can only accept ints for which you want to transfer ownership void u(unique_ptr<int>); // can only accept ints for which you are willing to share ownership void s(shared_ptr<int>); // accepts any int void h(int&);

The functions u and s have unique ownership semantics. u want to transfer ownership, s wants to share ownership. The function s includes a minor performance penalty. The reference counter of the std::shared_ptr has to be increased and decreased. This atomic operation takes a little bit of time.

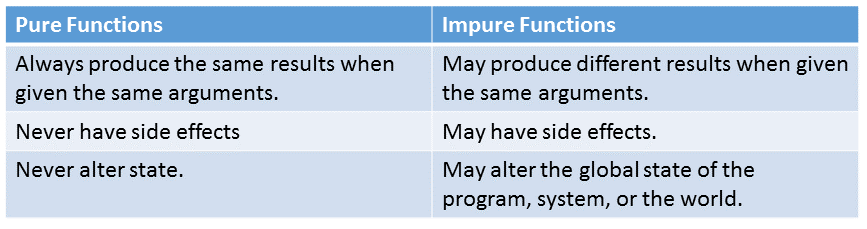

F.8: Prefer pure functions

A pure function is a function that always returns the same value when given the same arguments. This property is also often called referential transparency.

Pure functions have a few interesting properties:

These properties have far-reaching consequences because you can think about your function in isolation:

- The correctness of the code is easier to verify

- The refactoring and testing of the code are simpler

- You can memorize function results

- You can reorder pure functions or perform them on other threads.

Pure functions are often called mathematical functions.

By default, we have no pure functions in C++, such as the purely functional language Haskell, but constexpr functions are nearly pure. So pureness is based on discipline in C++.

Only for completeness. Template metaprogramming is a purely functional language embedded in the imperative language C++. If you are curious, read here about template metaprogramming.

F.9: Unused parameters should be unnamed

If you don’t provide names for the unused parameters, your program will be easier to read and will not get warnings about unused parameters.

What’s next

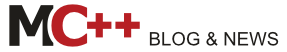

These were the rules about function definitions. I will write about the parameter passing to functions in the next post.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Phillip Diekmann, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, schnapper79, Seeker, and Sundareswaran Senthilvel.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!