Fences are Memory Barriers

The key idea of a std::atomic_thread_fence is to establish synchronization and ordering constraints between threads without an atomic operation.

std::atomic_thread_fence are called fences or memory barriers. So you immediately get the idea of what a std::atomic_thread_fence is all about.

A std::atomic_thread_fence prevents specific operations can overcome a memory barrier.

Memory barriers

But what does that mean? Specific operations which can not overcome a memory barrier. What kind of operations? From a bird’s perspective, we have two operations: Read and write or load and store. So the expression if(resultRead) return result is a load, followed by a store operation.

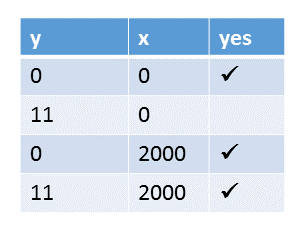

There are four different ways to combine load and store operations:

- LoadLoad: A load followed by a load.

- LoadStore: A load followed by a store.

- StoreLoad: A store followed by a load.

- StoreStore: A store followed by a store.

Of course, more complex operations consist of a load and store part (count++). But these operations didn’t contradict my general classification.

But what about memory barriers? If you place memory barriers between two operations like LoadLoad, LoadStore, StoreLoad, or StoreStore, you have the guarantee that specific LoadLoad, LoadStore, StoreLoad, or StoreStore operations can not be reordered. The risk of reordering is always given if non-atomics or atomics with relaxed semantics are used.

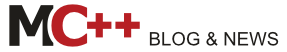

Typically, three kinds of memory barriers are used. They are called a full fence, acquire fence and release fence. Only to remind you. Acquire is a load; release is a store operation. So, what happens if I place one of the three memory barriers between the four load and store operations combinations?

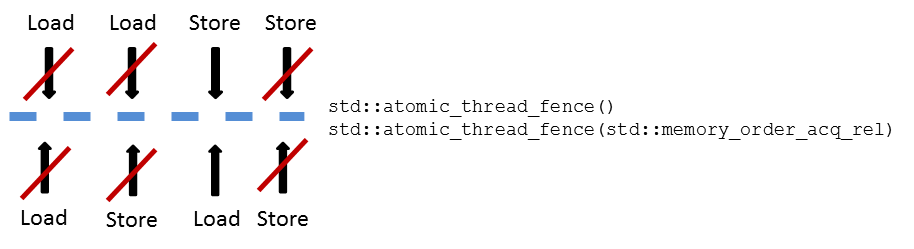

- Full fence: A full fence std::atomic_thread_fence() between two arbitrary operations prevents the reordering of these operations. But that guarantee will not hold for StoreLoad operations. They can be reordered.

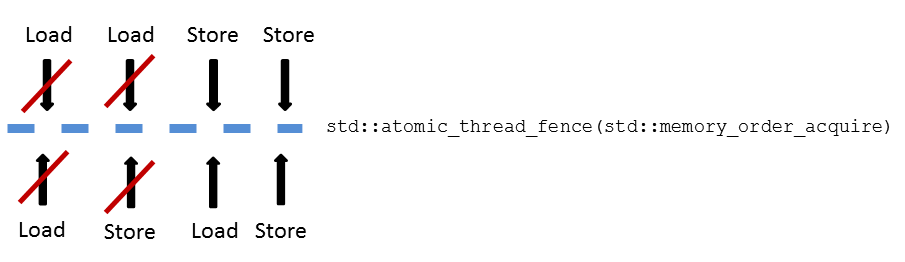

- Acquire fence: An acquire fence std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_acquire) prevents a read operation before an acquire fence can be reordered with a reading or write operation after the acquire fence.

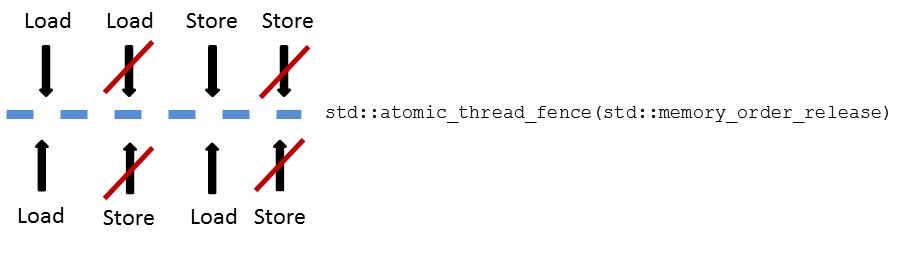

- Release fence: A release fence std::memory_thread_fence(std::memory_order_release) prevents a read or write operation before a release fence can be reordered with a write operation after a release fence.

I admit that I invested a lot of energy to get the definitions of an to acquire and release fence and their consequences for lock-free programming. Especially the subtle difference to the acquire-release semantics of atomic operations are not so easy to get. But, before I come to that point, I will illustrate the definitions with graphics.

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

Memory barriers illustrated

Which kind of operations can overcome a memory barrier? Have a look at the following three graphics. If the arrow is crossed with a red barn, the fence prevents this operation.

Full fence

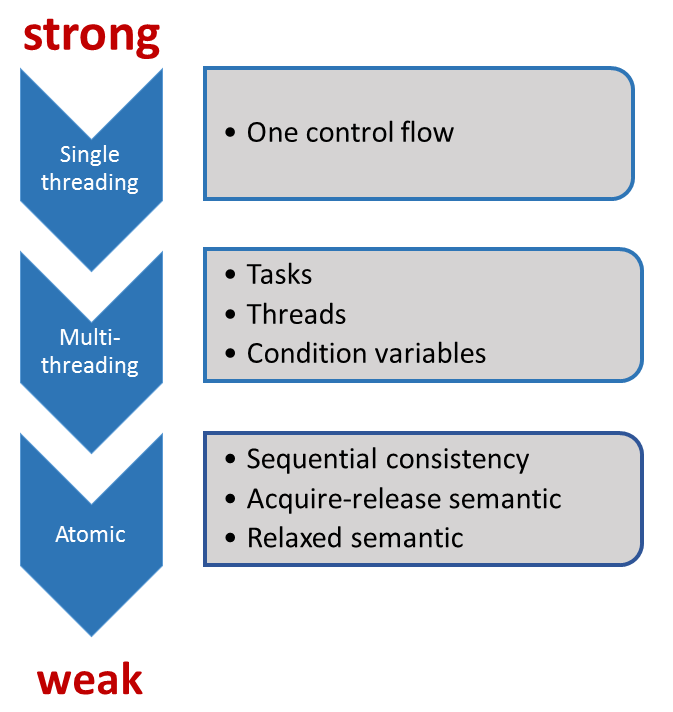

Of course, you can explicitly write instead of std::atomic_thread_fence() std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_seq_cst). Per default, sequential consistency is used for fences. Is sequential consistency used for a full fence, the std::atomic_thread_fence follows a global order.

Acquire fence

Release fence

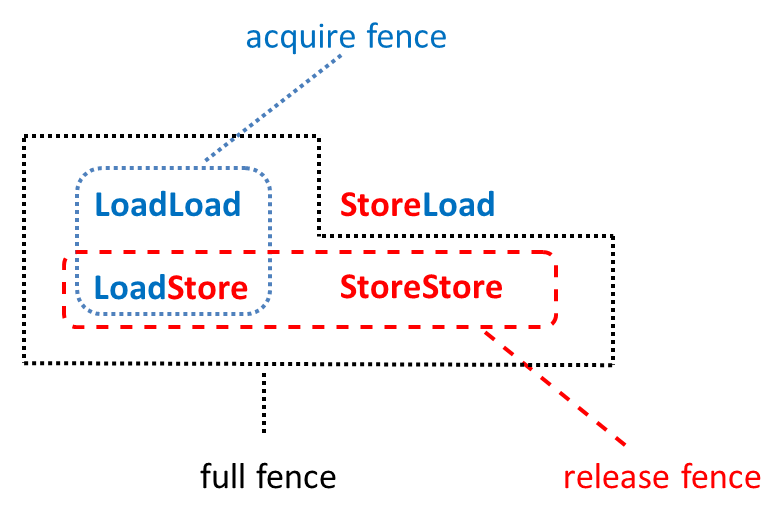

But I can depict the three memory barriers even more concisely.

Memory barriers at a glance

What’s next?

That was the theory. The practice will follow in the next post. In this post, I compare the first step, an acquire fence with an acquires operation, a release fence with a release operation. In the second step, I port a producer-consumer scenario with acquire release operations to fences.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Phillip Diekmann, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, and Seeker.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!