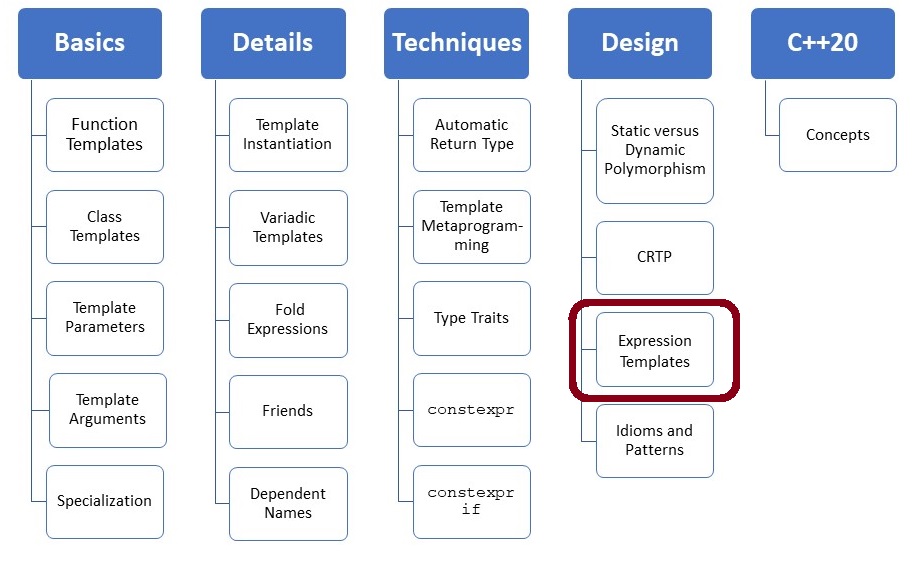

Expression Templates

Expression templates are “structures representing a computation at compile-time, which are evaluated only as needed to produce efficient code for the entire computation” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expression_templates). As needed, now we are at the center of lazy evaluation and the center of this post.

What problem do expression templates solve? Thanks to expression templates, you can eliminate superfluous temporary objects in expressions. What do I mean by superfluous temporary objects? My implementation of the class MyVector.

A first naive approach

MyVector is a simple wrapper for a std::vector<T>. The wrapper has two constructors (lines 12 and 15), knows its length (lines 18 – 20), and supports the reading (lines 23 – 25) and writing (lines 27 – 29) index access.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 |

// vectorArithmeticOperatorOverloading.cpp #include <iostream> #include <vector> template<typename T> class MyVector{ std::vector<T> cont; public: // MyVector with initial size MyVector(const std::size_t n) : cont(n){} // MyVector with initial size and value MyVector(const std::size_t n, const double initialValue) : cont(n, initialValue){} // size of underlying container std::size_t size() const{ return cont.size(); } // index operators T operator[](const std::size_t i) const{ return cont[i]; } T& operator[](const std::size_t i){ return cont[i]; } }; // function template for the + operator template<typename T> MyVector<T> operator+ (const MyVector<T>& a, const MyVector<T>& b){ MyVector<T> result(a.size()); for (std::size_t s= 0; s <= a.size(); ++s){ result[s]= a[s]+b[s]; } return result; } // function template for the * operator template<typename T> MyVector<T> operator* (const MyVector<T>& a, const MyVector<T>& b){ MyVector<T> result(a.size()); for (std::size_t s= 0; s <= a.size(); ++s){ result[s]= a[s]*b[s]; } return result; } // function template for << operator template<typename T> std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& os, const MyVector<T>& cont){ std::cout << std::endl; for (int i=0; i<cont.size(); ++i) { os << cont[i] << ' '; } os << std::endl; return os; } int main(){ MyVector<double> x(10,5.4); MyVector<double> y(10,10.3); MyVector<double> result(10); result= x+x + y*y; std::cout << result << std::endl; } |

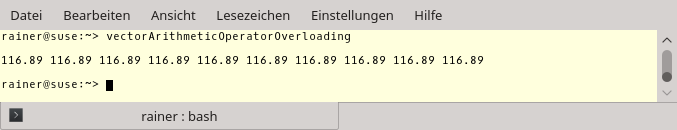

Thanks to the overloaded + operator (lines 34 – 41), the overloaded * operator (lines 44 – 51), and the overloaded output operator (lines 54 – 62), the objects x, y, and result feel like numbers.

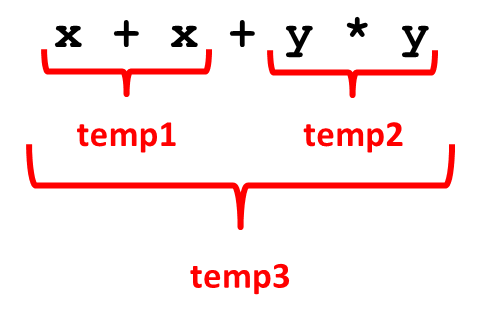

Why is this implementation naive? The answer is in the expression result= x+x + y*y. Three temporary objects are needed to evaluate the expression to hold the result of each arithmetic sub-expression.

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

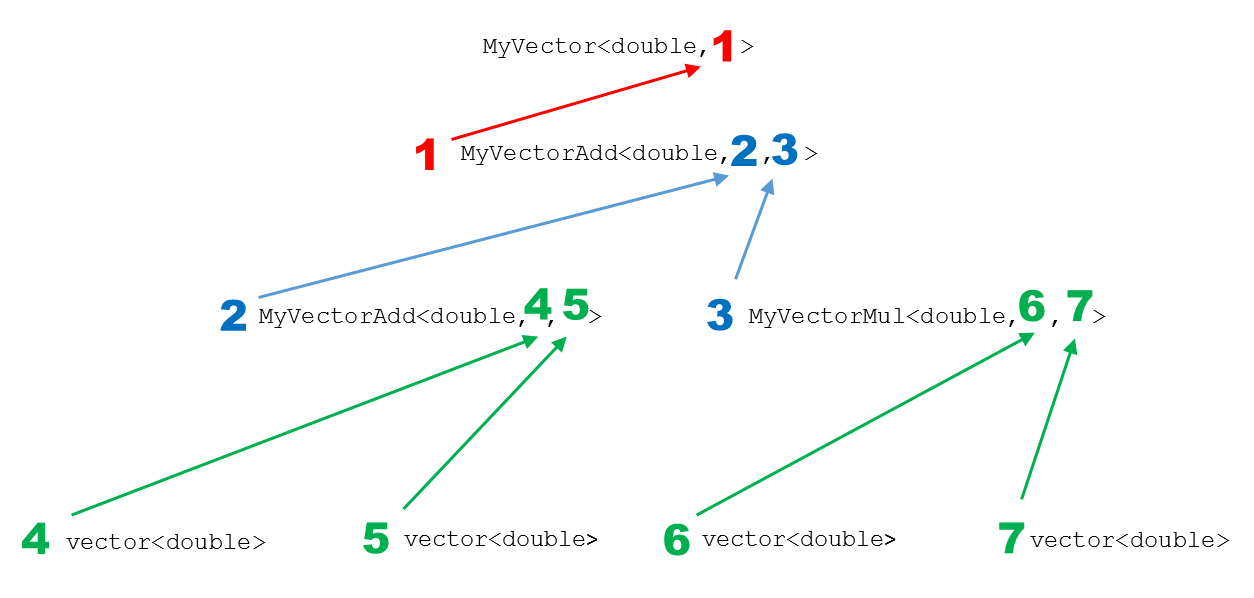

How can I get rid of the temporaries? The idea is simple. Instead of performing the vector operations greedy, I lazily create the expression tree for result[i] at compile time.

Expression templates

There are no temporaries needed for the expression result[i]= x[i]+x[i] + y[i]*y[i]. The assignment triggers the evaluation. Sadly, even in this simple usage, the code is not so easy to digest.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 |

// vectorArithmeticExpressionTemplates.cpp #include <cassert> #include <iostream> #include <vector> template<typename T, typename Cont= std::vector<T> > class MyVector{ Cont cont; public: // MyVector with initial size MyVector(const std::size_t n) : cont(n){} // MyVector with initial size and value MyVector(const std::size_t n, const double initialValue) : cont(n, initialValue){} // Constructor for underlying container MyVector(const Cont& other) : cont(other){} // assignment operator for MyVector of different type template<typename T2, typename R2> MyVector& operator=(const MyVector<T2, R2>& other){ assert(size() == other.size()); for (std::size_t i = 0; i < cont.size(); ++i) cont[i] = other[i]; return *this; } // size of underlying container std::size_t size() const{ return cont.size(); } // index operators T operator[](const std::size_t i) const{ return cont[i]; } T& operator[](const std::size_t i){ return cont[i]; } // returns the underlying data const Cont& data() const{ return cont; } Cont& data(){ return cont; } }; // MyVector + MyVector template<typename T, typename Op1 , typename Op2> class MyVectorAdd{ const Op1& op1; const Op2& op2; public: MyVectorAdd(const Op1& a, const Op2& b): op1(a), op2(b){} T operator[](const std::size_t i) const{ return op1[i] + op2[i]; } std::size_t size() const{ return op1.size(); } }; // elementwise MyVector * MyVector template< typename T, typename Op1 , typename Op2 > class MyVectorMul { const Op1& op1; const Op2& op2; public: MyVectorMul(const Op1& a, const Op2& b ): op1(a), op2(b){} T operator[](const std::size_t i) const{ return op1[i] * op2[i]; } std::size_t size() const{ return op1.size(); } }; // function template for the + operator template<typename T, typename R1, typename R2> MyVector<T, MyVectorAdd<T, R1, R2> > operator+ (const MyVector<T, R1>& a, const MyVector<T, R2>& b){ return MyVector<T, MyVectorAdd<T, R1, R2> >(MyVectorAdd<T, R1, R2 >(a.data(), b.data())); } // function template for the * operator template<typename T, typename R1, typename R2> MyVector<T, MyVectorMul< T, R1, R2> > operator* (const MyVector<T, R1>& a, const MyVector<T, R2>& b){ return MyVector<T, MyVectorMul<T, R1, R2> >(MyVectorMul<T, R1, R2 >(a.data(), b.data())); } // function template for < operator template<typename T> std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& os, const MyVector<T>& cont){ std::cout << std::endl; for (int i=0; i<cont.size(); ++i) { os << cont[i] << ' '; } os << std::endl; return os; } int main(){ MyVector<double> x(10,5.4); MyVector<double> y(10,10.3); MyVector<double> result(10); result= x+x + y*y; std::cout << result << std::endl; } |

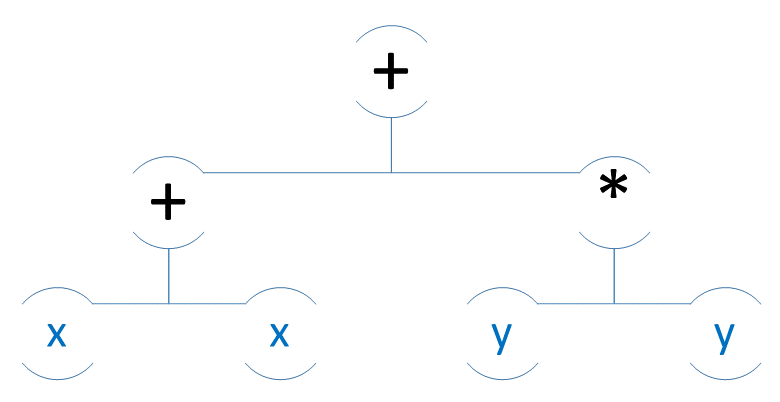

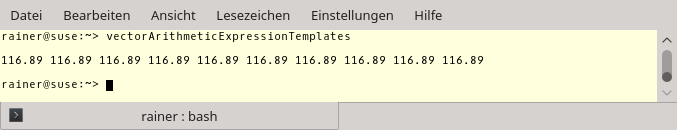

The key difference between the first naive implementation and this implementation with expression templates is that the overloaded + and + operators return in the case of the expression tree proxy objects. These proxies represent the expression tree (lines 94 and 100). The expression tree is only created but not evaluated. Lazy, of course. The assignment operator (lines 22 – 27) triggers the evaluation of the expression tree that needs no temporaries.

The result is the same.

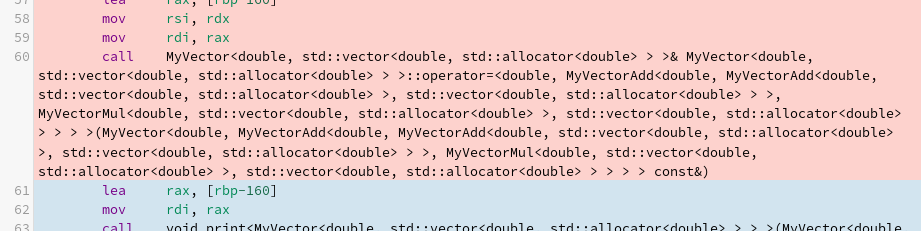

Suppose you were not able to follow my explanation, no problem. The assembler code of the program vectorArithmeticExpressionTemplates.cpp shows the magic.

Under the hood

Thanks to the compiler explorer on godbolt.org, it’s quite easy to have the assembler instructions.

The expression tree in line 60 is not so beautiful. But with a sharp eye, you can see the structure. For simplicity reasons, I ignored the std::allocator in my graphic.

What’s next?

With the next post, I will start the rework of my blog. That means I will rework old posts and write new posts to complete my stories. I will start in the next post with the multithreading features of C++17 and C++20. Here is an overview of all my posts.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, schnapper79, Seeker, and Sundareswaran Senthilvel.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!