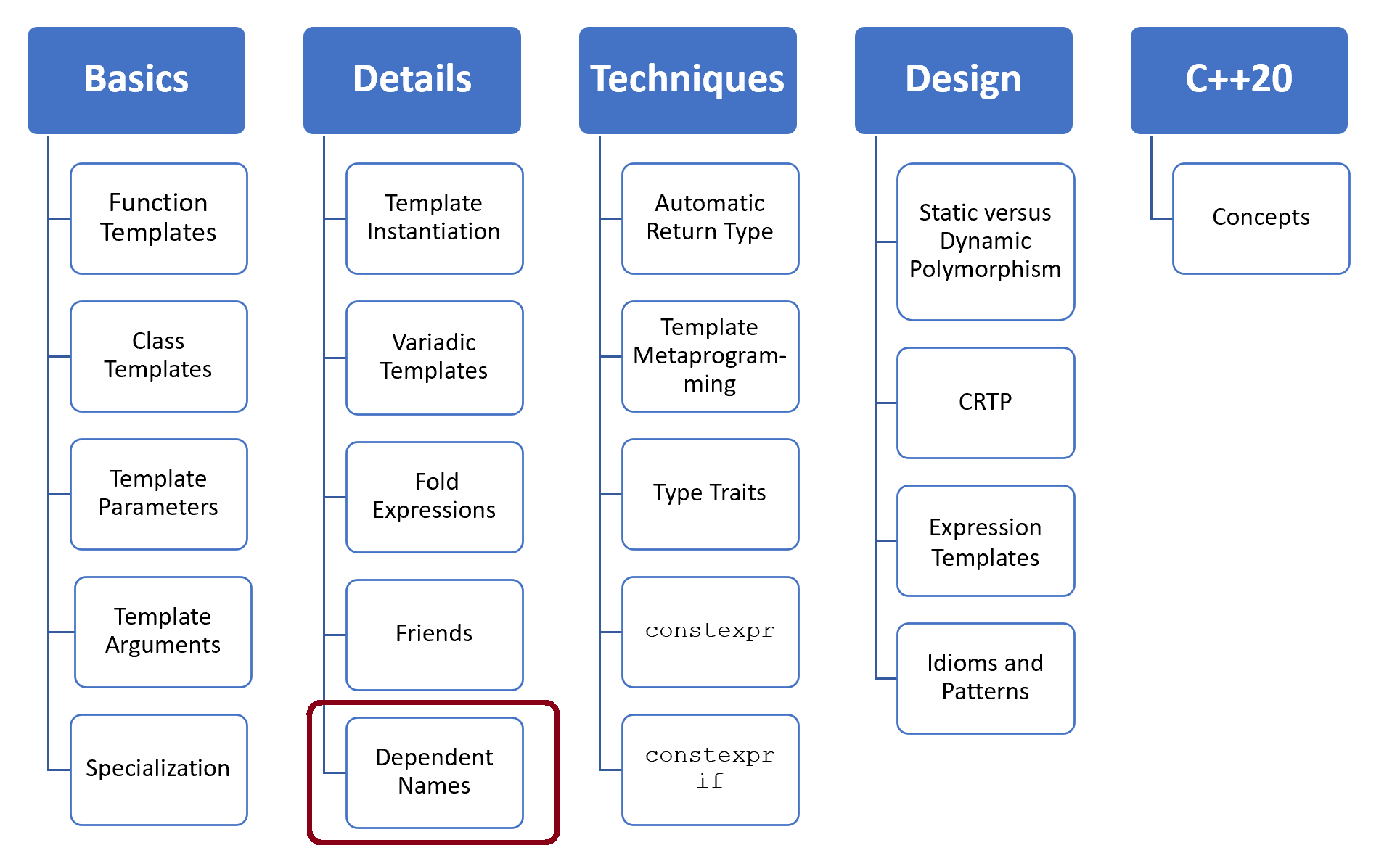

Dependent Names

A dependent name is essentially a name that depends on a template parameter. A dependent name can be a type, a non-type, or a template parameter. To express that a dependent name stands for a type or a template, you have to use the keywords typename or template.

Before I write about dependent names, I should write about template parameters.

Template Parameter

Template parameters can be types, non-types, and templates.

Types

Types are the most often used template parameters. Here are a few examples:

std::vector<int> myVec; std::map<std::string, int> myMap; std::lock_guard<std::mutex> myLockGuard;

Non-Types

Non-types can be a

- lvalue reference

- nullptr

- pointer

- enumerator

- integral types

- floating-point types (C++20)

- literal types (C++20)

Non-type template parameters are often just called NTTP.

Integrals are the most used non-types. std::array is the typical example because you have to specify at compile time the size of a std::array:

std::array<int, 3> myArray{1, 2, 3};

With C++20, you can also use two new non-types: floating-point types and literal types.

Literal Types must have the following two properties, essentially:

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Modernes C++ Mentoring

Do you want to stay informed: Subscribe.

- All base classes and non-static data members are public and non-mutable

- The types of all base classes and non-static data members are structural types or arrays of these

A literal type must have a constexpr constructor.

The following program uses floating-point types and literal types as template parameters.

// nonTypeTemplateParameter.cpp struct ClassType { constexpr ClassType(int) {} // (1) }; template <ClassType cl> // (2) auto getClassType() { return cl; } template <double d> // (3) auto getDouble() { return d; } int main() { auto c1 = getClassType<ClassType(2020)>(); auto d1 = getDouble<5.5>(); // (4) auto d2 = getDouble<6.5>(); // (4) }

ClassType has a constexpr constructor (1) and can be used as a template argument (2). The function template getDouble (3) accepts only doubles. I want to emphasize it explicitly that each call of the function template getDouble (4) with a new argument triggers the instantiation of a new function template specialization of getDouble. This means that two instantiations for the doubles 5.5 and 6.5 are created.

Templates

Templates can be template parameters; in this case, they are called template template parameters.

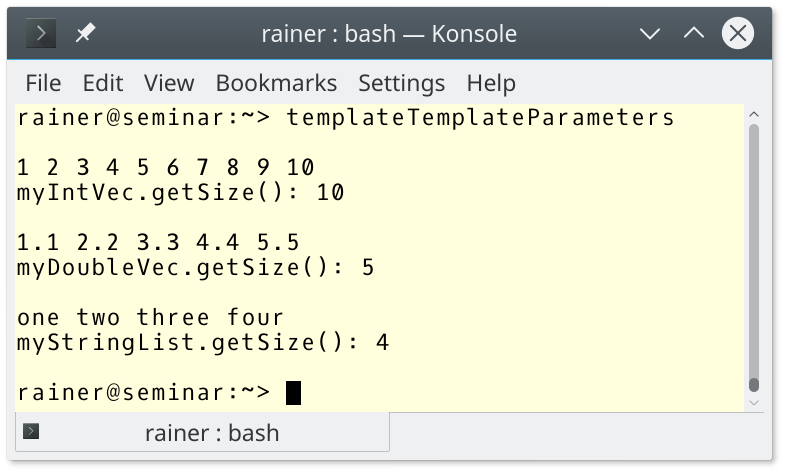

// templateTemplateParameters.cpp #include <iostream> #include <list> #include <vector> #include <string> template <typename T, template <typename, typename> class Cont > // (1) class Matrix{ public: explicit Matrix(std::initializer_list<T> inList): data(inList) { // (2) for (auto d: data) std::cout << d << " "; } int getSize() const{ return data.size(); } private: Cont<T, std::allocator<T>> data; // (3) }; int main() { std::cout << '\n'; // (4) Matrix<int, std::vector> myIntVec{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}; std::cout << std::endl; std::cout << "myIntVec.getSize(): " << myIntVec.getSize() << '\n'; std::cout << std::endl; Matrix<double, std::vector> myDoubleVec{1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4, 5.5}; // (5) std::cout << std::endl; std::cout << "myDoubleVec.getSize(): " << myDoubleVec.getSize() << '\n'; std::cout << std::endl; // (6) Matrix<std::string, std::list> myStringList{"one", "two", "three", "four"}; std::cout << std::endl; std::cout << "myStringList.getSize(): " << myStringList.getSize() << '\n'; std::cout << '\n'; }

Matrix is a simple class template that can be initialized by a std::initializer_list (line 2). A Matrix can be used with a std::vector (line 4 and line 5) or a std::list (line 6) to hold its values. So far, nothing special.

Line 1 declares a class template that has two template parameters. The first parameter is the type of the elements, and the second parameter stands for the container. Look at the second parameter: template <typename, typename> class Cont>. This means the second template argument should be a template requiring two template parameters. The first template parameter is the type of elements the container stores, and the second is the defaulted allocator a container of the standard template library has. The allocator has a default value, such as in the case of a std::vector. The allocator depends on the type of elements.

template< typename T, typename Allocator = std::allocator<T> > class vector;

Line 3 shows the allocator used in this internally used container. The matrix can be instantiated with all containers of the kind: container< type of the elements, allocator of the elements>. This is true for the sequence containers such as std::vector, std::deque, or std::list. std::array and std::forward_list would fail because std::array needs an additional non-type for specifying its size at compile-time, and std::forward_list does not support the size method.

Now, I can write about dependent names.

Dependent Names

What is a dependent name? A dependent name is essentially a name that depends on a template parameter. Here are a few examples based on cppreference.com:

template<typename T> struct X : B<T> // "B<T>" is dependent on T { typename T::A* pa; // "T::A" is dependent on T void f(B<T>* pb) { static int i = B<T>::i; // "B<T>::i" is dependent on T pb->j++; // "pb->j" is dependent on T } };

Now, the fun starts. A dependent name can be a type, a non-type, or a template parameter. The name lookup is the big difference between non-dependent and dependent names.

- Non-dependent names are looked up at the point of the template definition.

- Dependent names are looked up at the point of the template instantiation.

When you use a dependent name in a template declaration, the compiler has no idea whether this name refers to a type, a non-type, or a template parameter. In this case, the compiler assumes that the dependent name refers to a non-type, which may be wrong. This is when you have to give the compiler a hint.

Before I show you two examples, I must write about an exception to this rule. You can skip my next few words if you want to get a general idea and jump directly to the next section. The exception is if the name refers to the current instantiation in the template definition; the compiler can deduce the name at the point of the template definition. Here are a few examples:

template <typename T> class A { A* p1; // A is the current instantiation A<T>* p2; // A<T> is the current instantiation ::A<T>* p4; // ::A<T> is the current instantiation A<T*> p3; // A<T*> is not the current instantiation }; template <typename T> class A<T*> { A<T*>* p1; // A<T*> is the current instantiation A<T>* p2; // A<T> is not the current instantiation }; template <int I> struct B { static const int my_I = I; static const int my_I2 = I + 0; static const int my_I3 = my_I; B<my_I>* b3; // B<my_I> is the current instantiation B<my_I2>* b4; // B<my_I2> is not the current instantiation B<my_I3>* b5; // B<my_I3> is the current instantiation };

Finally, I came to the critical idea of my post. If a dependent name could be a type, a non-type, or a template, you must give the compiler a hint.

Use typename if the Dependent Name is a Type

After such a long introduction, the following program snippet clarifies it.

template <typename T> void test(){ std::vector<T>::const_iterator* p1; // (1) typename std::vector<T>::const_iterator* p2; // (2) }

Without the typename keyword in line 2, the name std::vector<T>::const_iterator in line 2 would be interpreted as a non-type and, consequently, the * stands for multiplication and not for a pointer declaration. This is exactly what happens in line (1).

Similarly, if your dependent name should be a template, you must give the compiler a hint.

Use .template if the Dependent Name is a Template

Honestly, this syntax looks a bit weird.

template<typename T> struct S { template <typename U> void func(){} } template<typename T> void func2(){ S<T> s; s.func<T>(); // (1) s.template func<T>(); // (2) }

It’s the same story as before. Compare lines 1 and 2. When the compiler reads the name s.func (line 1), it interprets it as non-type. This means the < sign stands for the comparison operator, but not opening the square bracket of the template argument of the generic method func. In this case, you must specify that s.func is a template, such as in line 2: s.template func.

Here is the essence of this post in one sentence: When you have a dependent name, use typename to specify that the dependent name is a type or use .template to specify that the dependent name is a template.

What’s next?

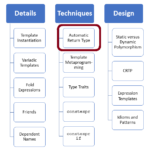

In my next post, I will present automatic return types. They are often a lifesaver when it comes to function templates.

Thanks a lot to my Patreon Supporters: Matt Braun, Roman Postanciuc, Tobias Zindl, G Prvulovic, Reinhold Dröge, Abernitzke, Frank Grimm, Sakib, Broeserl, António Pina, Sergey Agafyin, Андрей Бурмистров, Jake, GS, Lawton Shoemake, Jozo Leko, John Breland, Venkat Nandam, Jose Francisco, Douglas Tinkham, Kuchlong Kuchlong, Robert Blanch, Truels Wissneth, Mario Luoni, Friedrich Huber, lennonli, Pramod Tikare Muralidhara, Peter Ware, Daniel Hufschläger, Alessandro Pezzato, Bob Perry, Satish Vangipuram, Andi Ireland, Richard Ohnemus, Michael Dunsky, Leo Goodstadt, John Wiederhirn, Yacob Cohen-Arazi, Florian Tischler, Robin Furness, Michael Young, Holger Detering, Bernd Mühlhaus, Stephen Kelley, Kyle Dean, Tusar Palauri, Juan Dent, George Liao, Daniel Ceperley, Jon T Hess, Stephen Totten, Wolfgang Fütterer, Matthias Grün, Ben Atakora, Ann Shatoff, Rob North, Bhavith C Achar, Marco Parri Empoli, Philipp Lenk, Charles-Jianye Chen, Keith Jeffery, Matt Godbolt, Honey Sukesan, bruce_lee_wayne, Silviu Ardelean, schnapper79, Seeker, and Sundareswaran Senthilvel.

Thanks, in particular, to Jon Hess, Lakshman, Christian Wittenhorst, Sherhy Pyton, Dendi Suhubdy, Sudhakar Belagurusamy, Richard Sargeant, Rusty Fleming, John Nebel, Mipko, Alicja Kaminska, Slavko Radman, and David Poole.

| My special thanks to Embarcadero |  |

| My special thanks to PVS-Studio |  |

| My special thanks to Tipi.build |  |

| My special thanks to Take Up Code |  |

| My special thanks to SHAVEDYAKS |  |

Modernes C++ GmbH

Modernes C++ Mentoring (English)

Rainer Grimm

Yalovastraße 20

72108 Rottenburg

Mail: schulung@ModernesCpp.de

Mentoring: www.ModernesCpp.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!